click here for a walkthrough of the installation

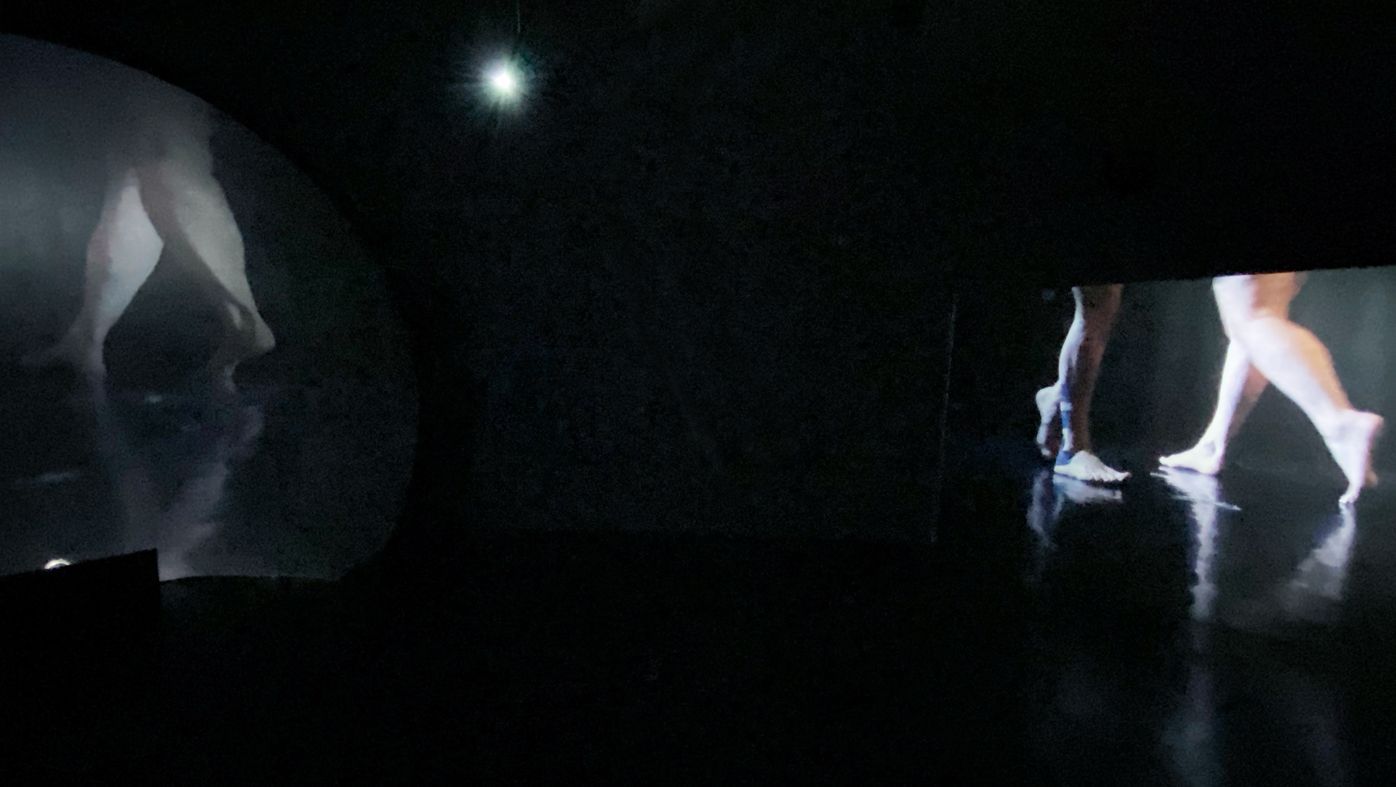

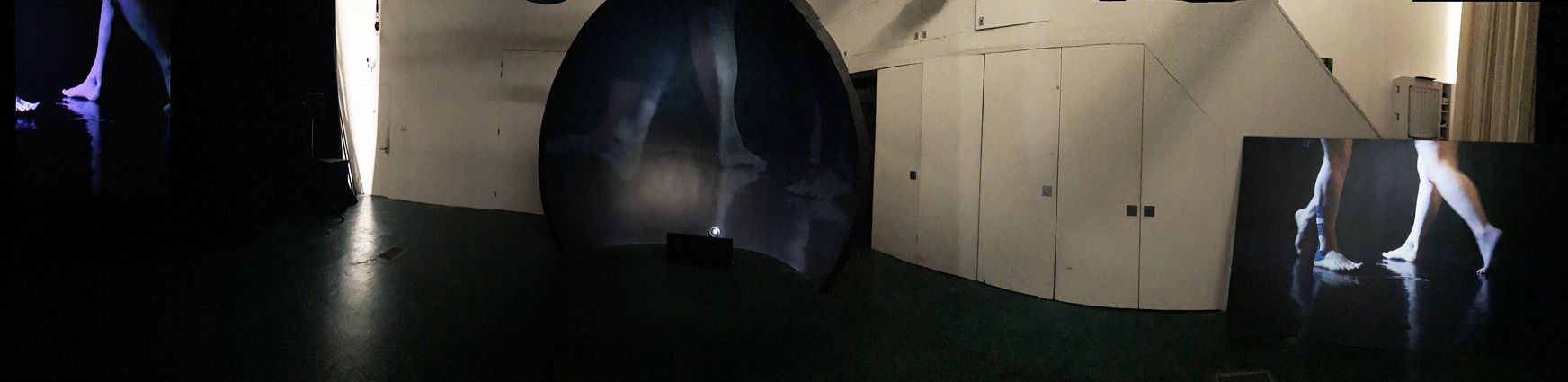

‘Tracking Parallel’ at Empathy & Risk, 2025

press release:

Over the past year, Richard Ducker has been working with New York-based contemporary dance choreographer Heidi Latsky investigating the relationship between the moving body in space and the moving image on screen. Rather than documenting a single performance Ducker looks to find an equivalence between the two mediums.

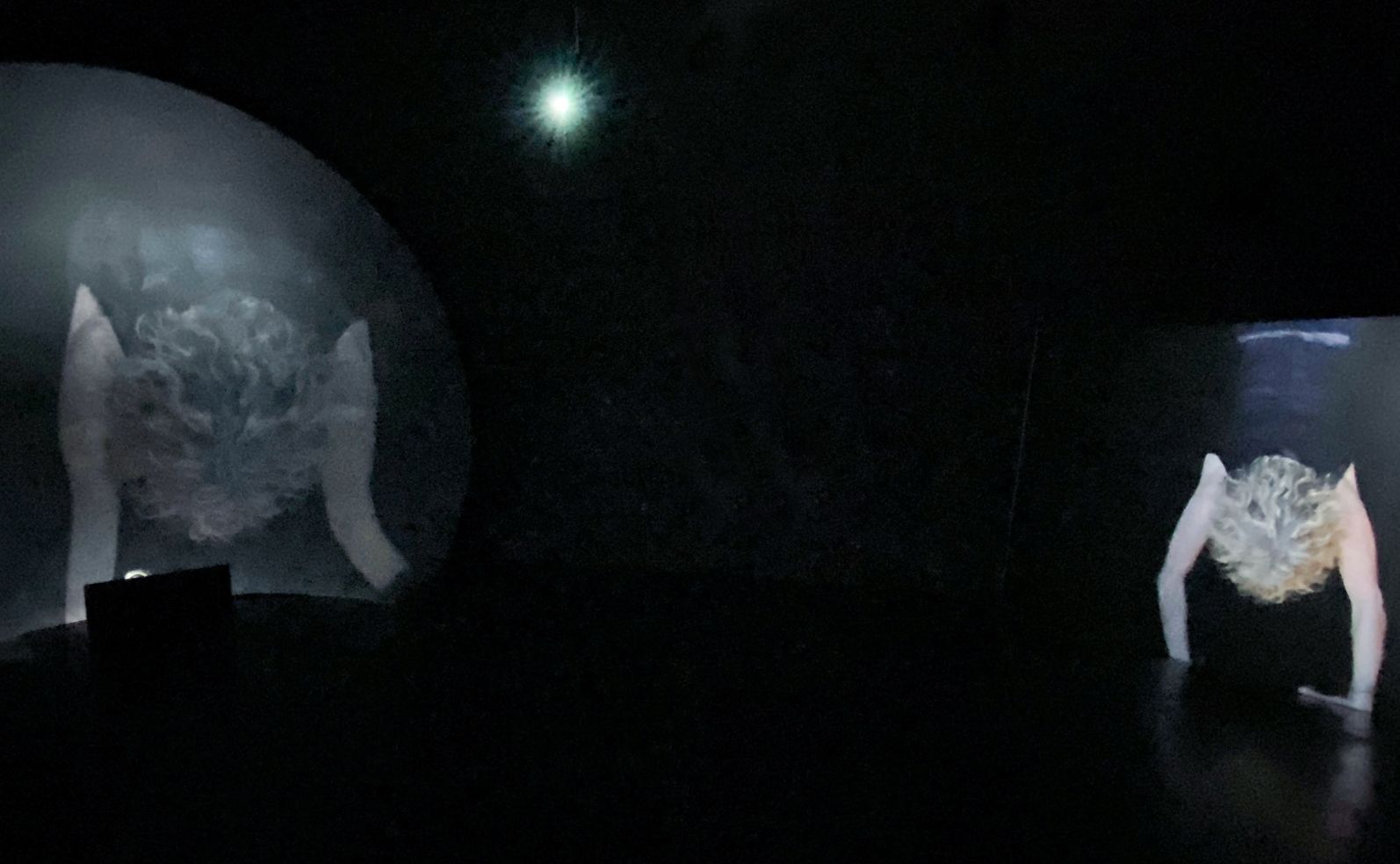

Heidi Latsky works with a range of dancers who are diverse in race, age and body shape that at times deliberately question the usual archetypes of dance movement. Tracking Parallel was originally devised to make a work about the parallel lives we all led during the enforced isolation of the Covid lockdowns, but it gained more immediacy in response to Heidi’s own recent health crisis. Dance is perhaps the oldest and most primal form of human expression. It is an act of freedom, of escaping constraint, and in this context an articulation of what it means to be alive. The work speaks to personal survival in states of contingency and temporal fragility.

The film explores this through a visual lexicon that examines how the image functions in time within the fluid nature of performance. Using the moving image as a device of seduction and spectacle, the body here is both sensual and corporeal. It articulates being inside a performance where it is the fragments of expression that present its precariousness.

Tracking Parallel, 36 mins, 2025

Some thoughts on the ideas behind Tracking Parallel

DEVELOPING THE CONCEPT

The relationship between the content of the dance and what I wanted from the film were different. Heidi’s choreography and my film were pursuing two different agendas, which produced an interesting and fruitful dichotomy.

Introduced by a mutual friend, initially I didn't know much about Heidi or how I was going to film. I knew that I wanted to make a film that put the viewer cinematically inside a performance. Rather than passively documenting a performance, my intention was to explore the idea of the body moving in space. Heidi’s background was working with dancers with various disabilities, and this often influenced the content of her work. As our conversations developed, it became clear that for Heidi, ‘Tracking Parallel’ reflected and responded to the psychological repercussions of the isolation caused by the pandemic lockdowns.

While the choreography wasn’t specific in its representation, the underlying premise was more of an evocative presence. This allowed me the space to explore my interest in taking the camera into the dance and investigate the notion of editing as a form of choreography, as a form of rhythm making.

EDITING AS A FORM OF CHOREOGRAPHY

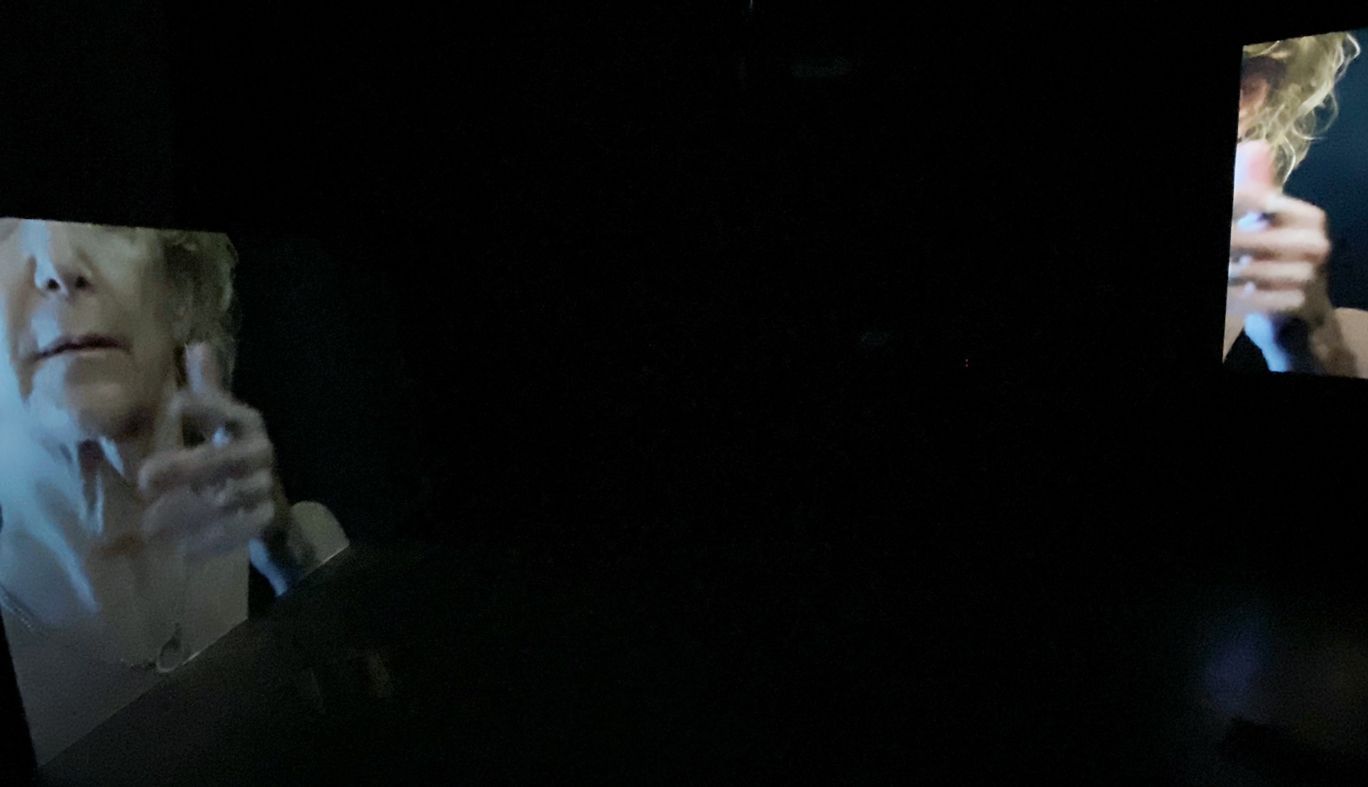

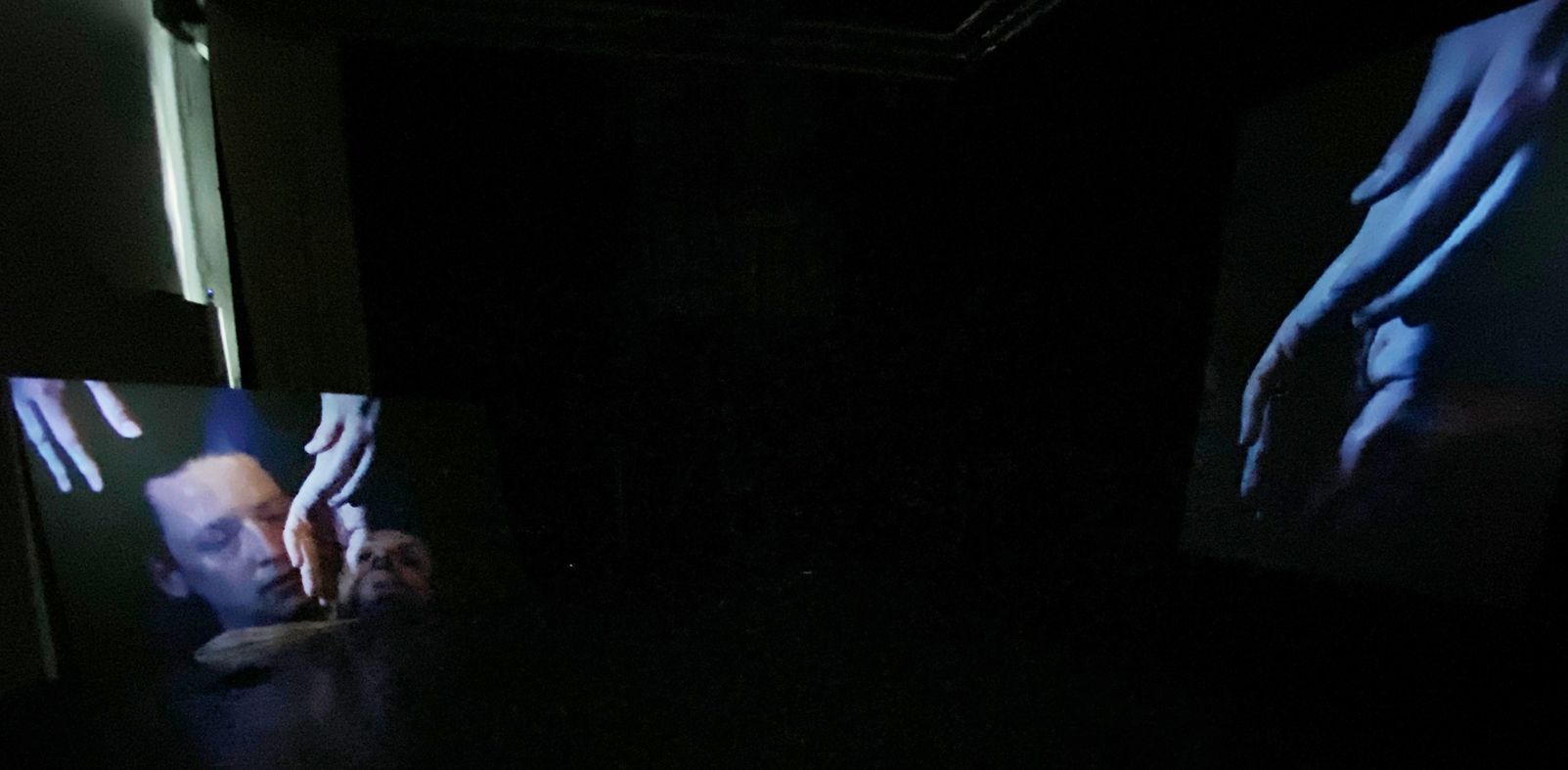

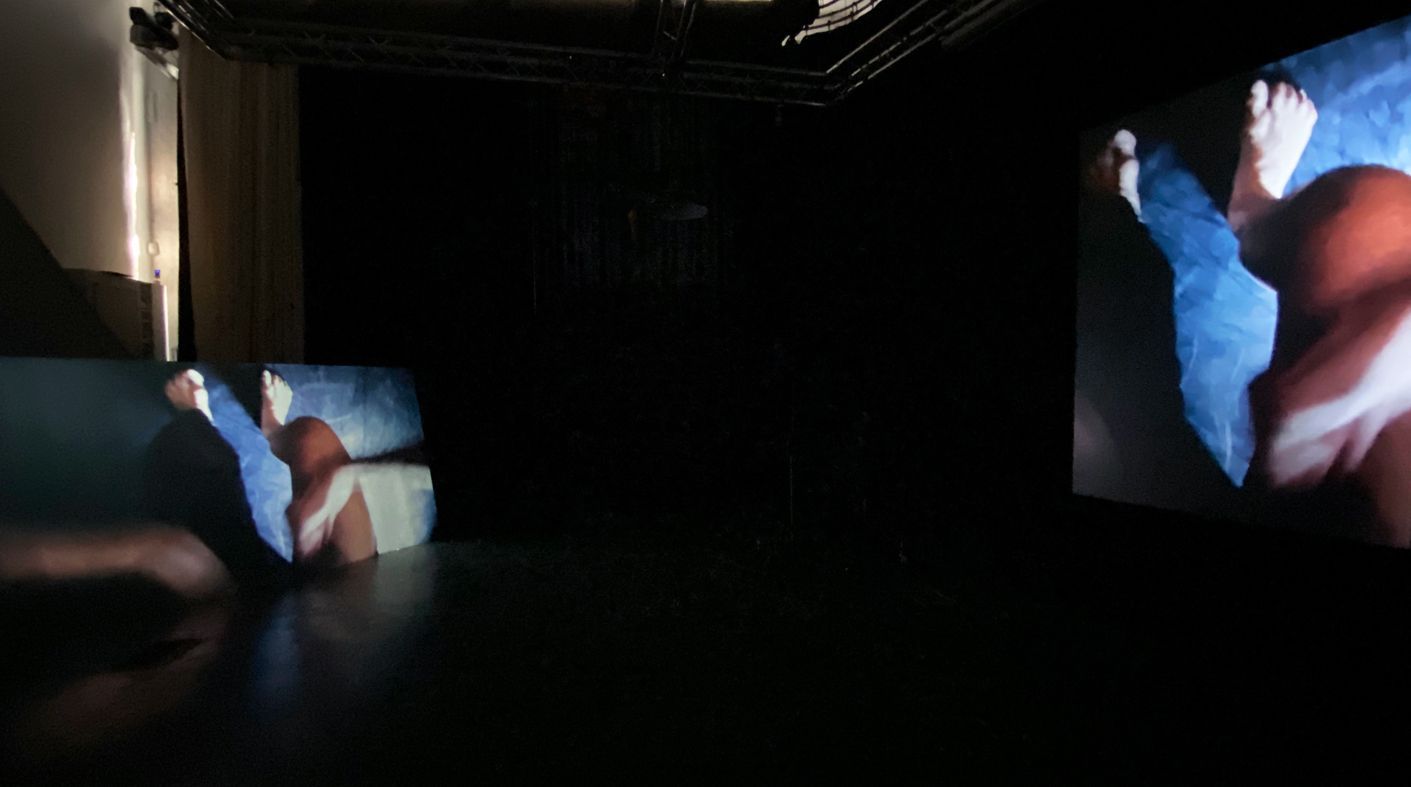

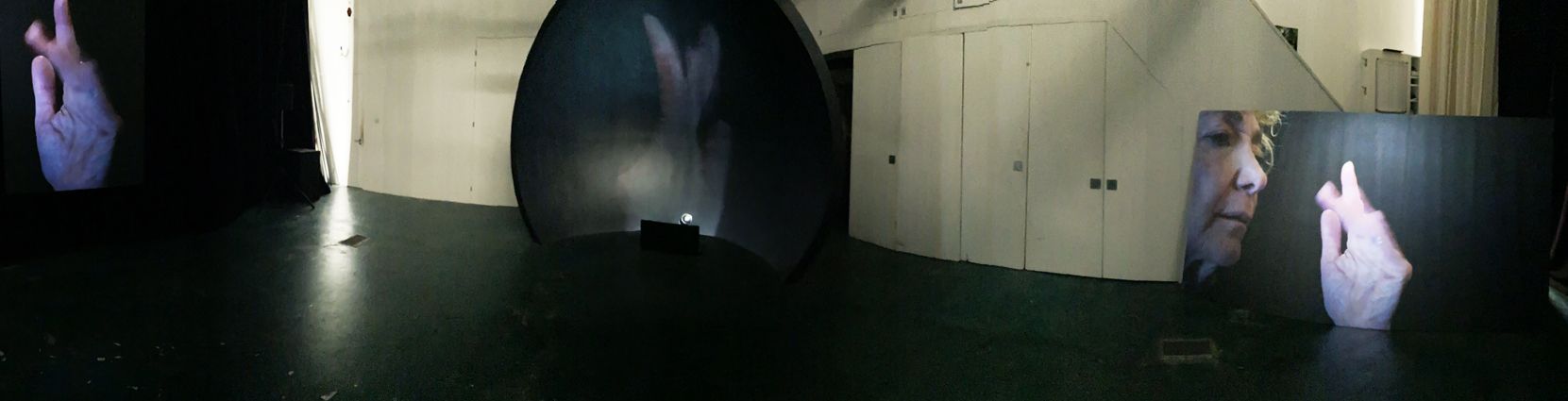

Filming extended takes of the performance was very difficult, unless the camera was stationary on a tripod. However, I also wanted was to capture on film was how the dancer might experience the performance. That you would occasionally see a dancer’s hand or a knee, so the film’s fragmentary nature fits with the intention of what I wanted by taking the viewer inside the performance.

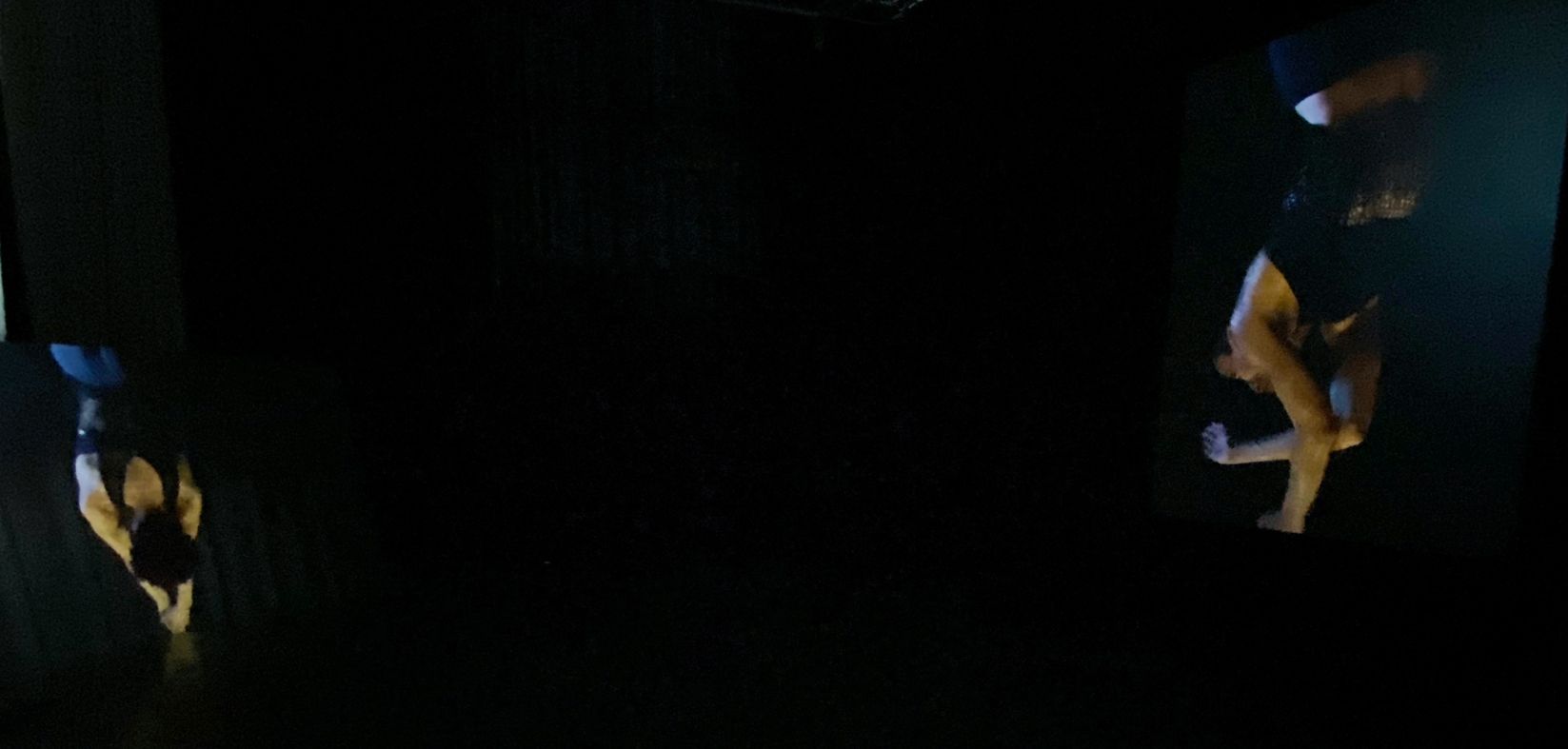

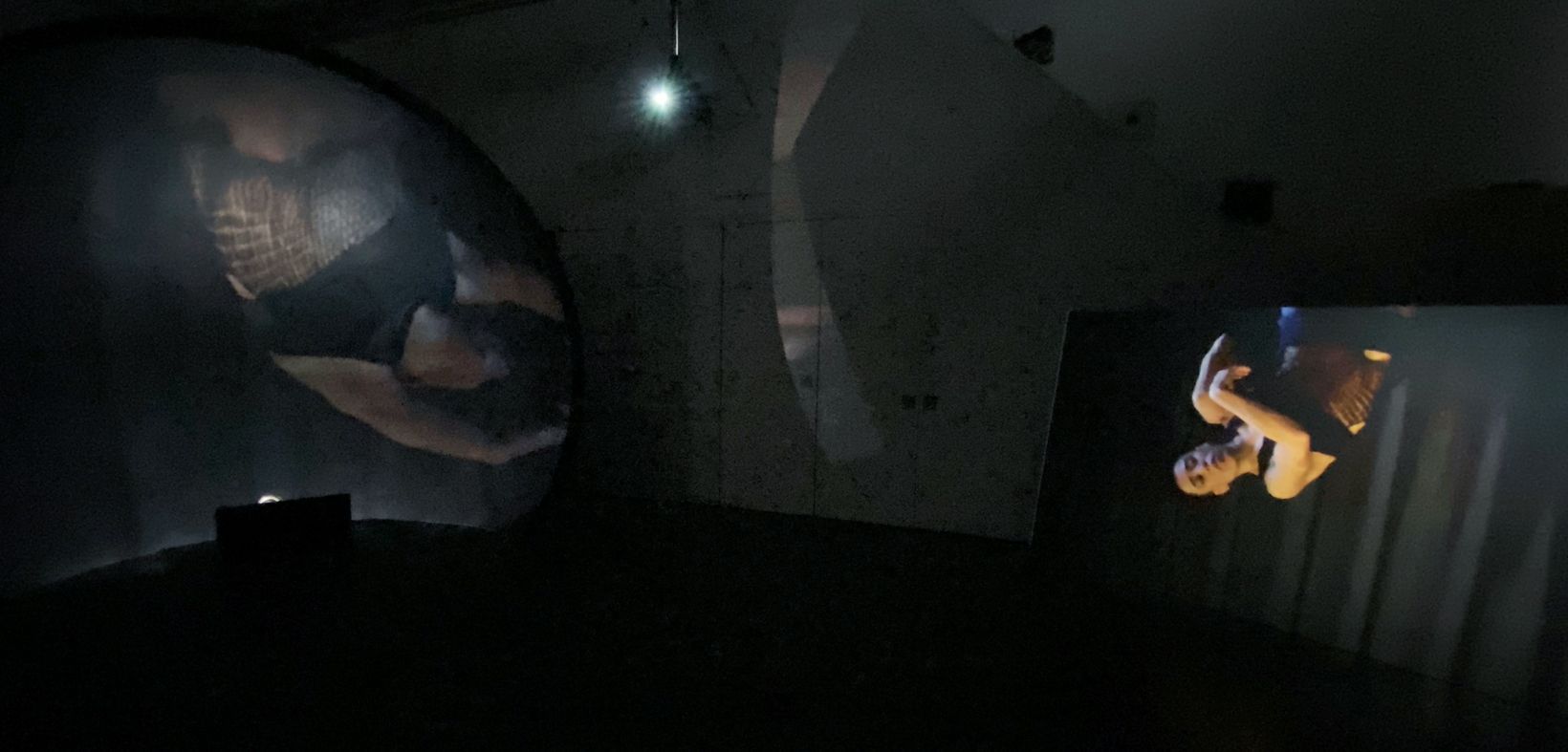

By contrast, there are certain slow motion sequences of dancers that are overlaid or suspended upside down, which is outside of choreography. They are the language of cinema only.

In that sense, the selection of shots, the rhythm and structure, editing as a form of choreography is very much a metaphor to get closer to the idea of a performance. Because some footage is recorded with GoPros on the dancers I didn't know what I was getting until I got home and downloaded the film. I then spliced it in with short clips of other elements of the performance. These quick edit sequences had very little to do with the choreography that was being performed. Instead, the clips are spliced together like highlights of the complete dance compressed into a couple of minutes. I used that twice as a kind of bridge between other moments in the performance. Like a bridge in a song.

There are edits that have certain speeds and tempos, gaps and quiet moments that are not dissimilar to how you might put a dance together. Where it differs is that I can focus in on a detail, I can repeat an action, I can reverse a piece of performance, and I can crop - all of which is either physically hard or impossible to do on stage. So I have at my disposal possibilities as part of the editing process that a choreographer does not. What you see on screen is actually very different to what you would experience in the audience of a performance. The moments that are zoomed in, the repeated motions, the isolated parts were all part of the richness of the editing process. This was how the film came alive.

This editing process produces a narrative arc that provides the film’s architecture. However, the notion of a narrative is problematic because it implies there might be a story. I wanted a formal structure without a story being told but there is a beginning, middle and an end that takes you on a journey.

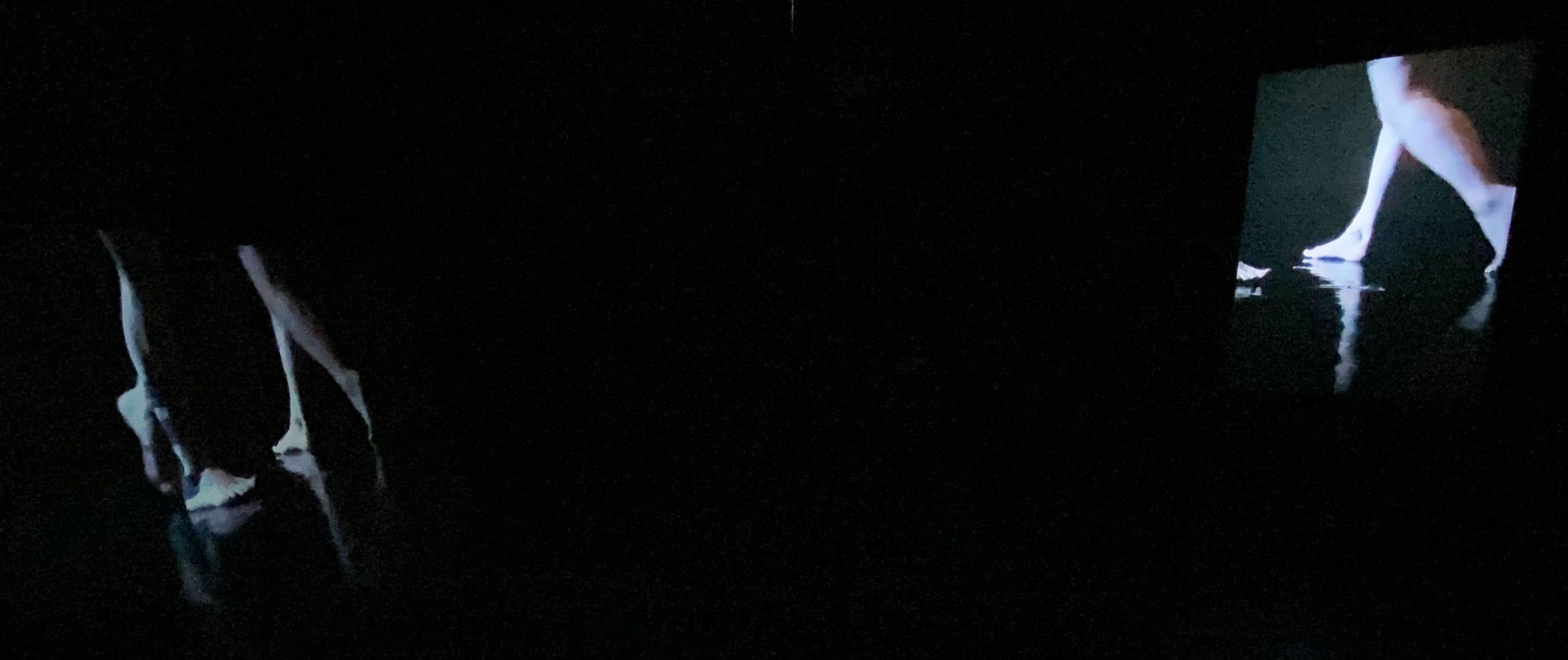

There were elements in the film that I knew I wanted before we started. One of them was the sound of footsteps and close up of feet. Another was close up of various details like hands, faces, and limbs. And then to begin with these details before opening up the viewer to more visual information about what is happening. The other thing I knew I wanted, which was to give that sense of being inside a performance, was to use GoPros on the dancers.

All this I had in my mind before I knew what I was dealing with in terms of the choreography. Heidi then sent me footage of her rehearsals for me to choose the sequences I wanted to film. Based on the footage she sent I selected the sequences that I thought would work for the film. So I never filmed a complete performance - it was always sequences out of context. Everything that I filmed was a work in progress for Heidi and In that sense was material for the film. That was beneficial for me because it would have been much harder to film a finished performance, as that would have been a piece of documentation.

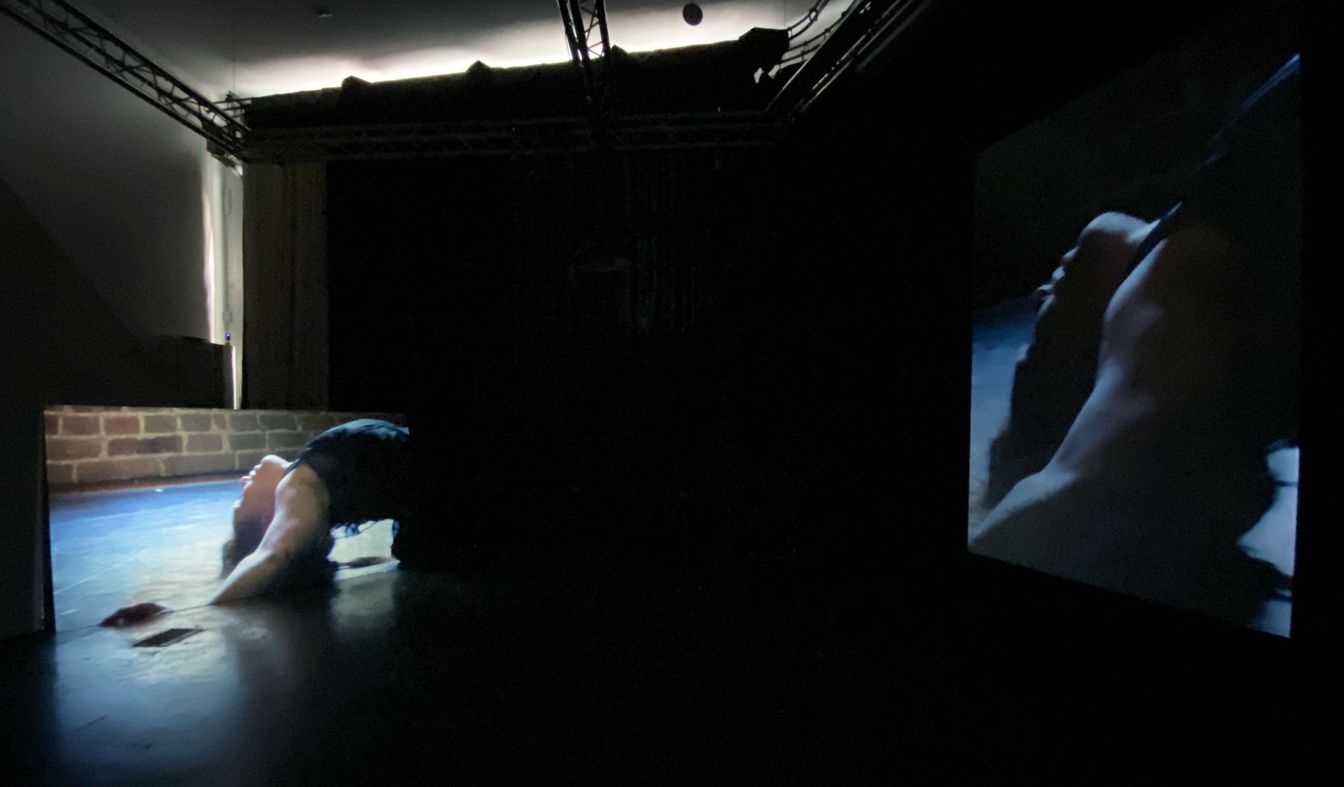

Instead, I’ve separated elements to focus on the abstract and the dynamic to arrive at an understanding of spatial motion. By disorienting the viewer and by offering only glimpses, I wanted to introduce the feeling of watching a dance performance, but you can't see it. Instead, you're catching moments, as if you are inside it.

SOUNDTRACK

For the soundtrack, I knew that I wanted the sound of the footsteps, especially as part of this introduction to the film. It was functional, about the performative, while being simultaneously obscure. I knew that I wanted a rhythmic soundtrack for the GoPro section, but I didn't want music in any traditional sense. So all the preliminary editing was done without sound.

Later during the editing process, Heidi sent one of the early rehearsals that she had done which included a soundtrack of an MRI machine that she had been working on with a composer. It developed into a soundscape with ambient and rhythmic sections. I knew immediately that that it was a perfect fit for the film, not only because of the backstory of Heidi’s brain tumor which coincided with this project, but it also captured many of the emotions we all experienced during lockdown. The sound is both ambient and uncomfortable. For the rest of the film, I felt it needed silence, to act like a negative space. So there's actually quite a lot which has no sound at all.

There are only two or three points in the film where the sound is edited specifically to the image. The rest of the time it sort of seeps in and out. These broad strokes create the tension between content and structure, that is present within the soundtrack.

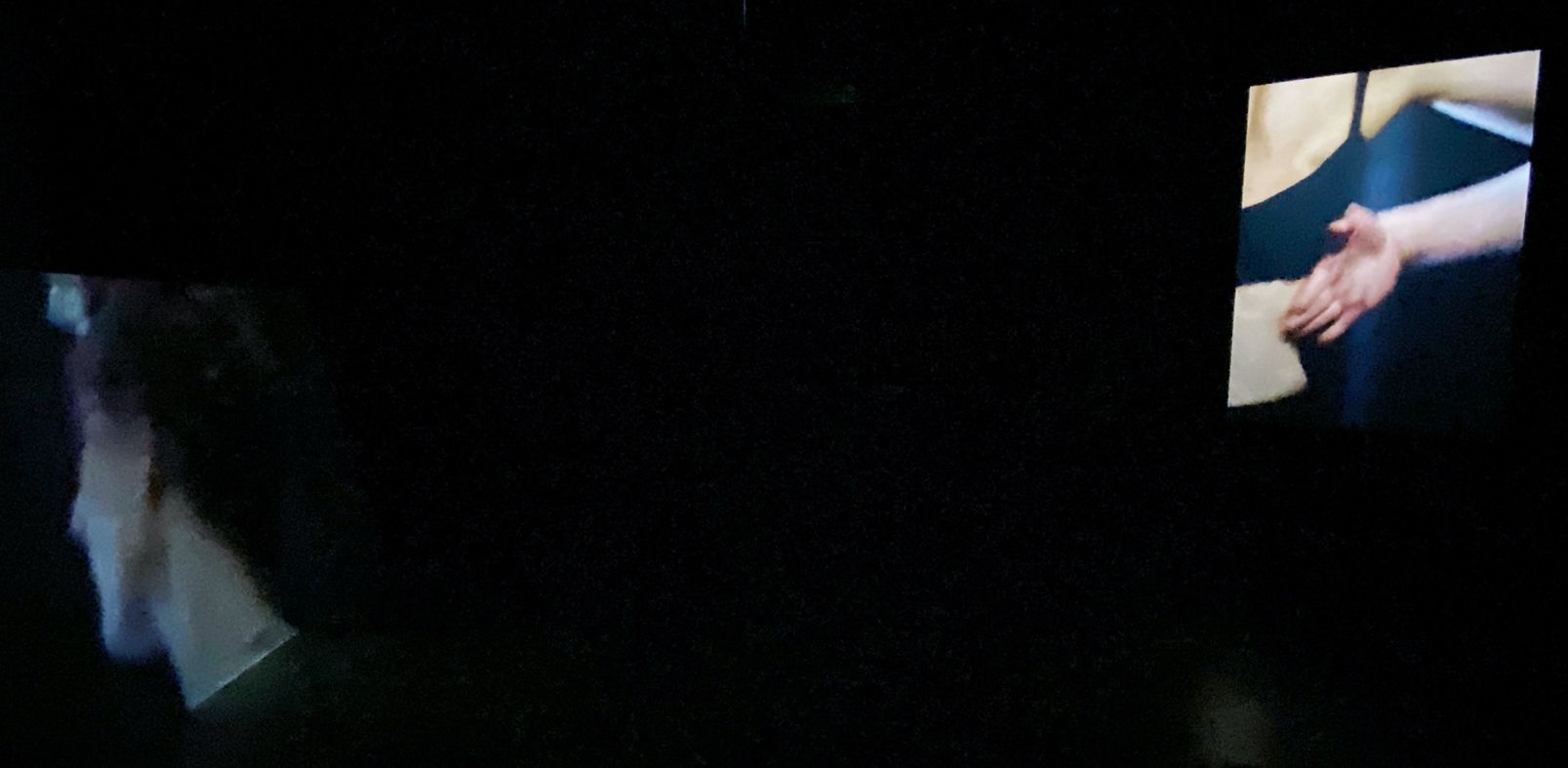

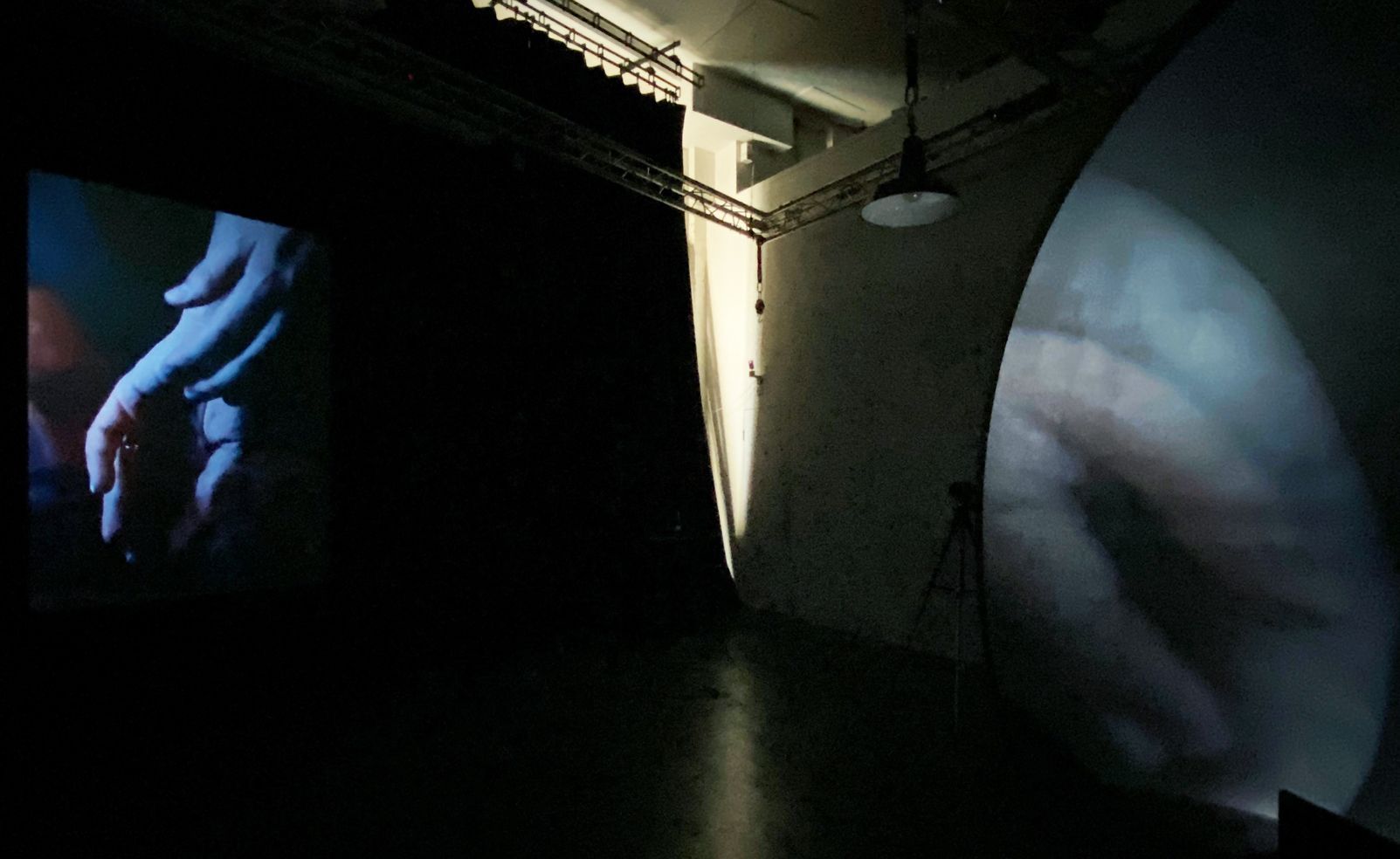

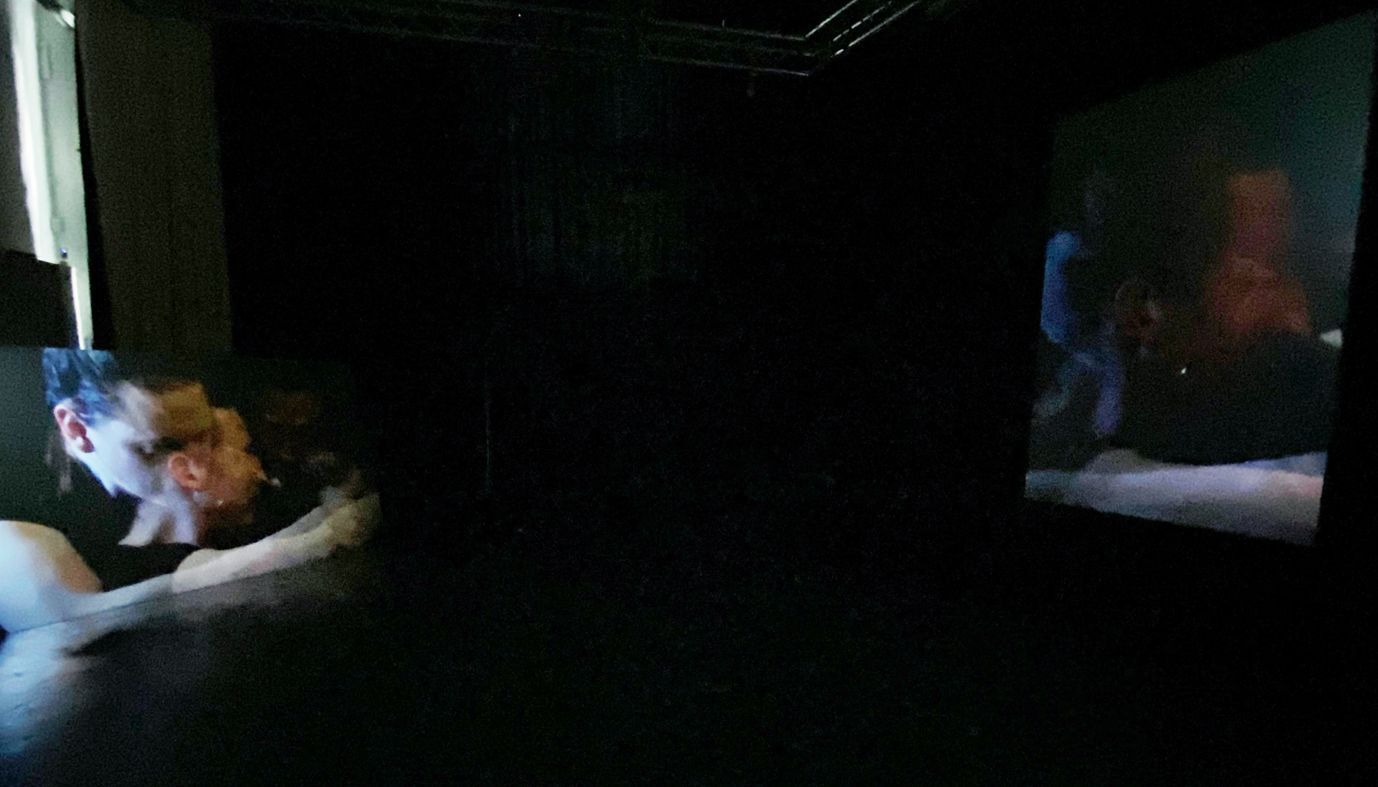

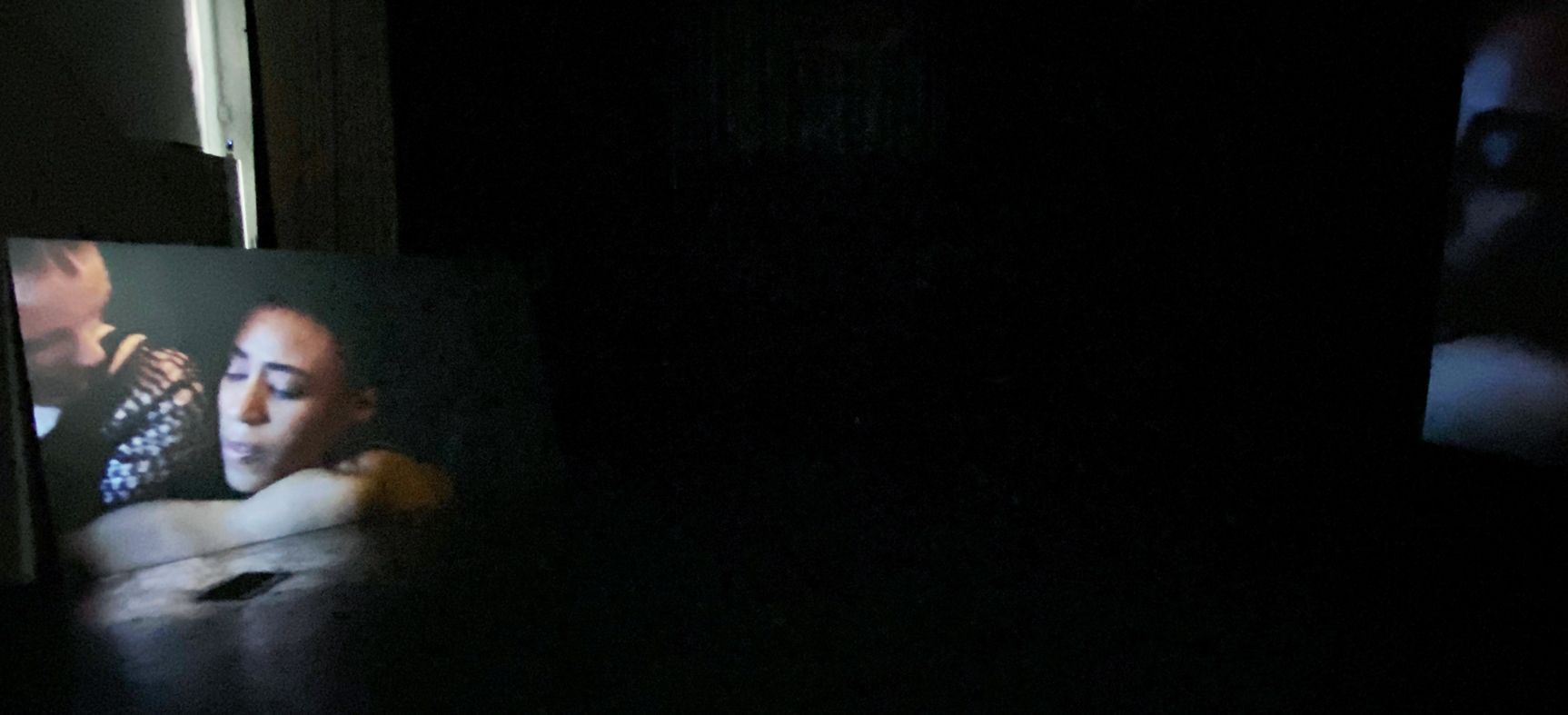

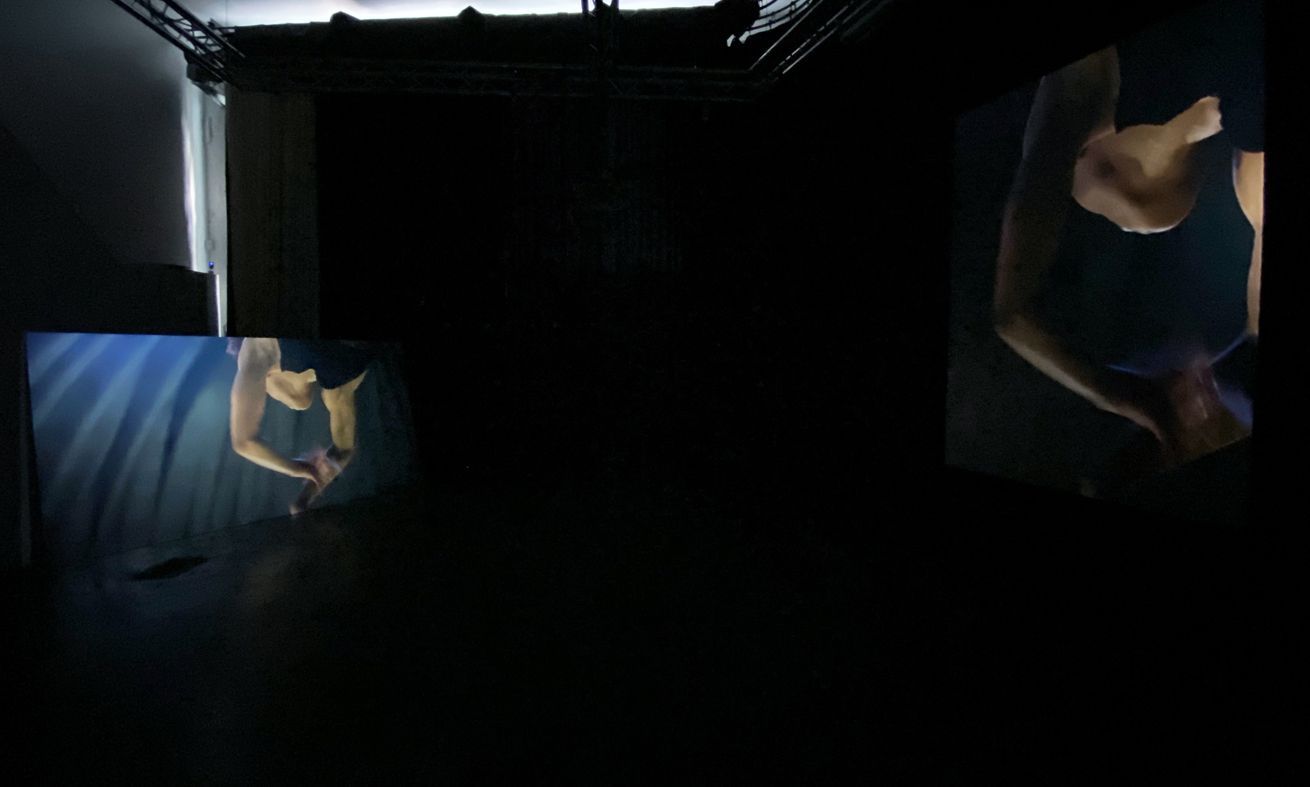

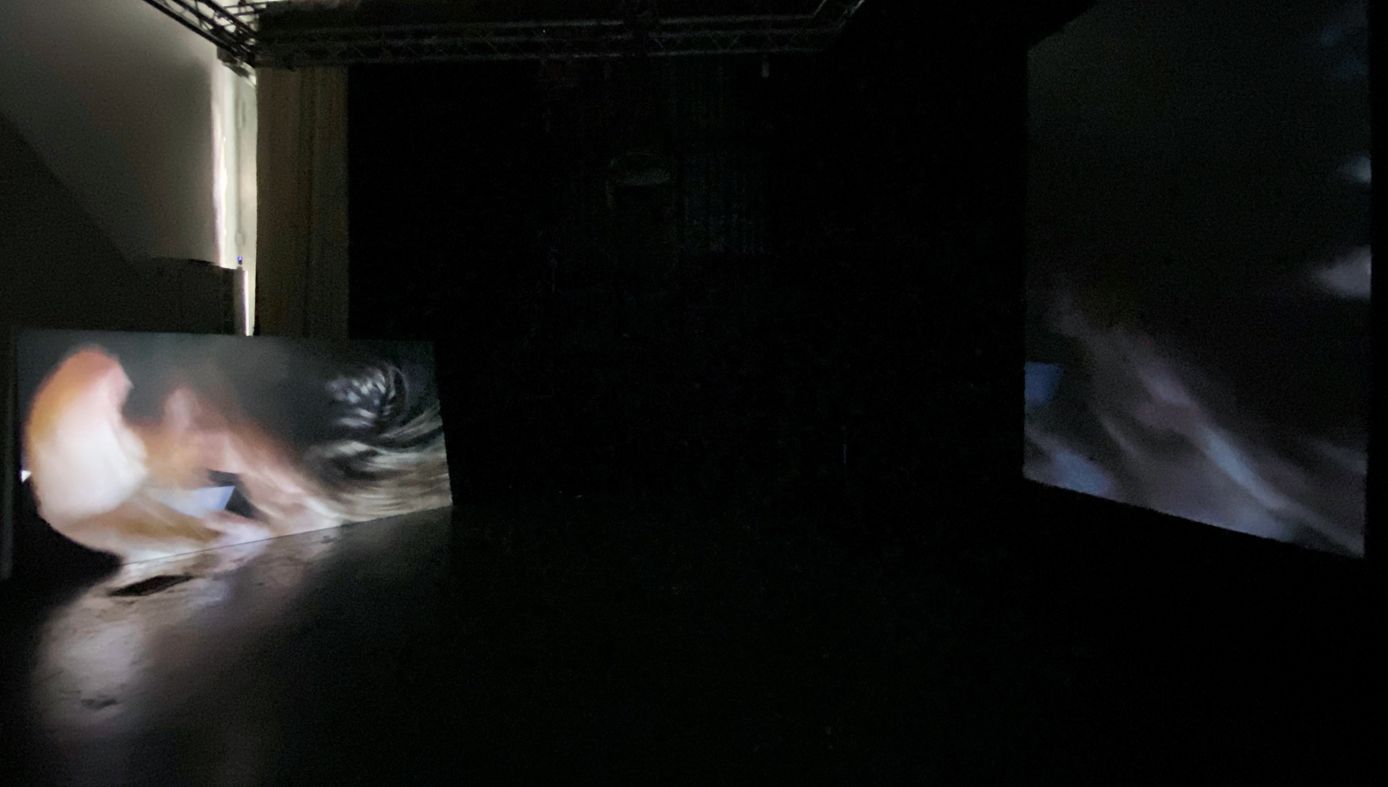

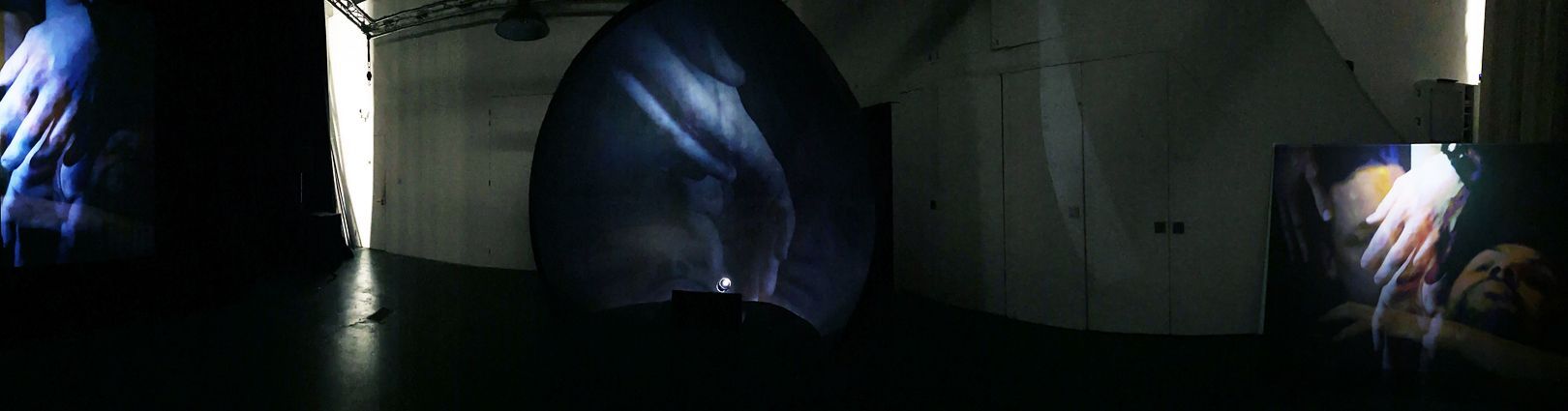

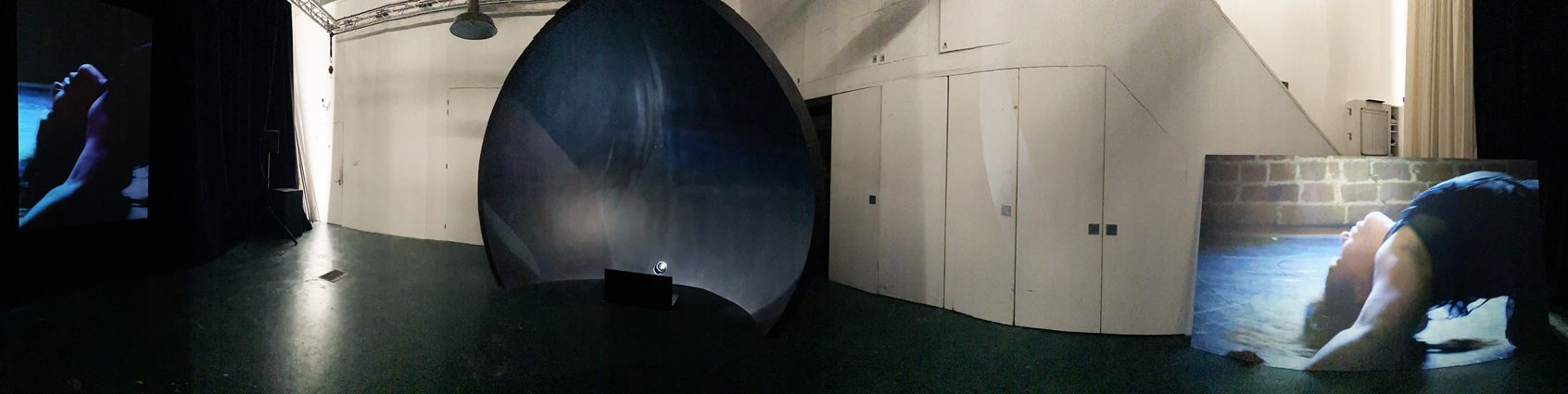

These editorial processes it opened up a dialogue about the viewer's relationship between the passive and active spectacle in relation to performance and cinema. With the three screen version, I wanted to make the spectacle present in a more dialectical way, so the viewer could take some agency by deciding where to sit or stand or move around the space, in between the screens. By contrast, the single channel foregrounds the editing process in the more traditional language of cinema. So the rhythm is not the same in both.

THREE CHANNEL INSTALLATION vs. SINGLE CHANNEL EDIT

From the outset of this project, I knew that I wanted to present ‘Tracking Parallel’ as a three screen installation. But as I was pulling it together, I found it made sense to arrange my material as a single edit first, and then break it up into three separate channels, creating two different ways of seeing / experiencing the same thing.

Selection and arrangement of the footage gives the film its structure - it's not just ambient visuals. The real challenge of editing was to condense and concentrate the expanded performance. In part that was to consider the attention span of the viewer at a screening of a single channel edit. By contrast, the 3 channel edit is longer and looped, to allow the possibility of entering and leaving at the viewer’s discretion. Straddling these two options through the editing of the same footage was interesting. The 3 channel edit gave me more freedom to be slightly looser and to experiment with how the 3 screens could be used to show images at different times, or repeat moments on each screen sequentially, or simply have one playing and two left blank. That way the rhythm of the work operated spatially and allows the viewer to choose their own edit. There’s an agency there. The viewer becomes active rather than the passive participant of a single channel screening. It gets closer to the idea that dance is about the body in time and space and places the viewer into that position.

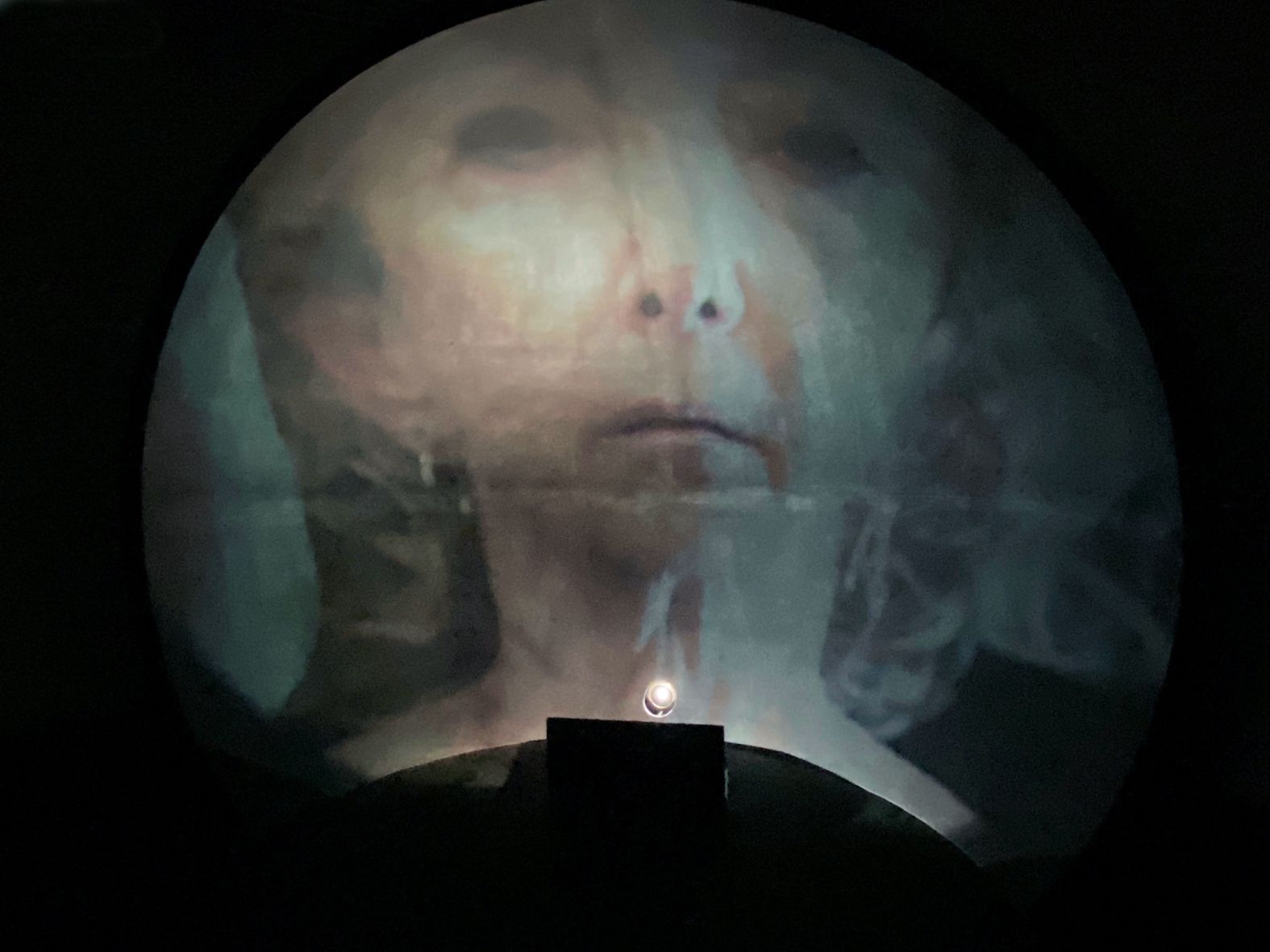

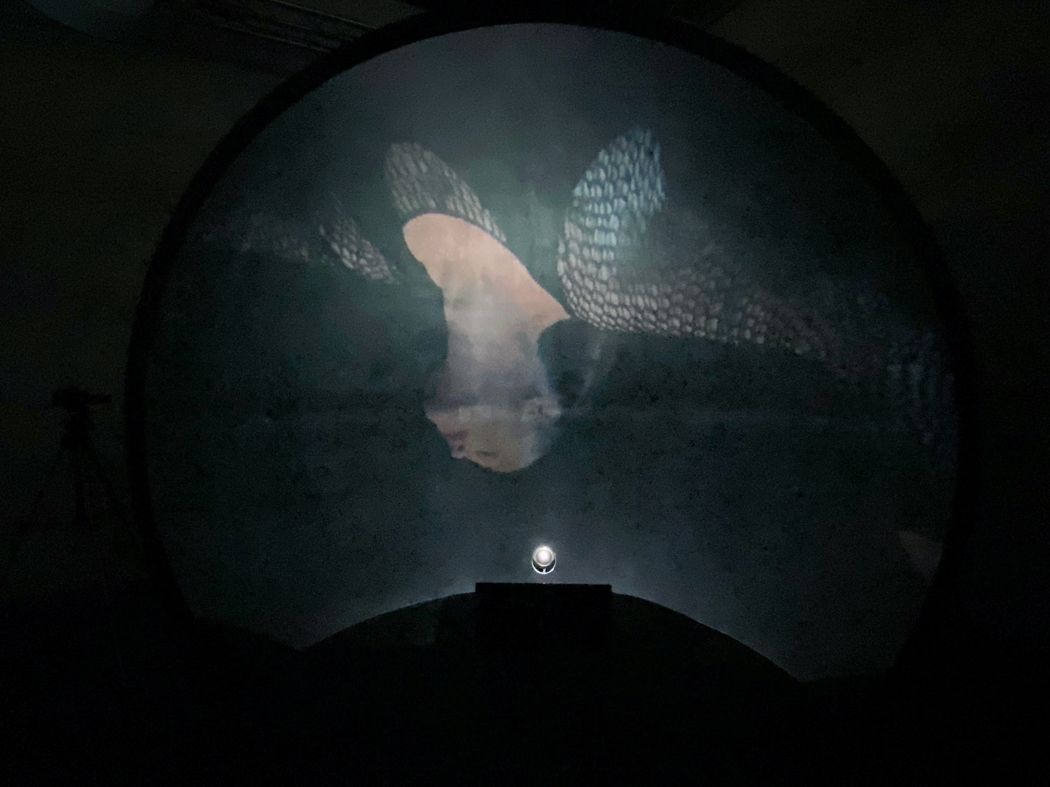

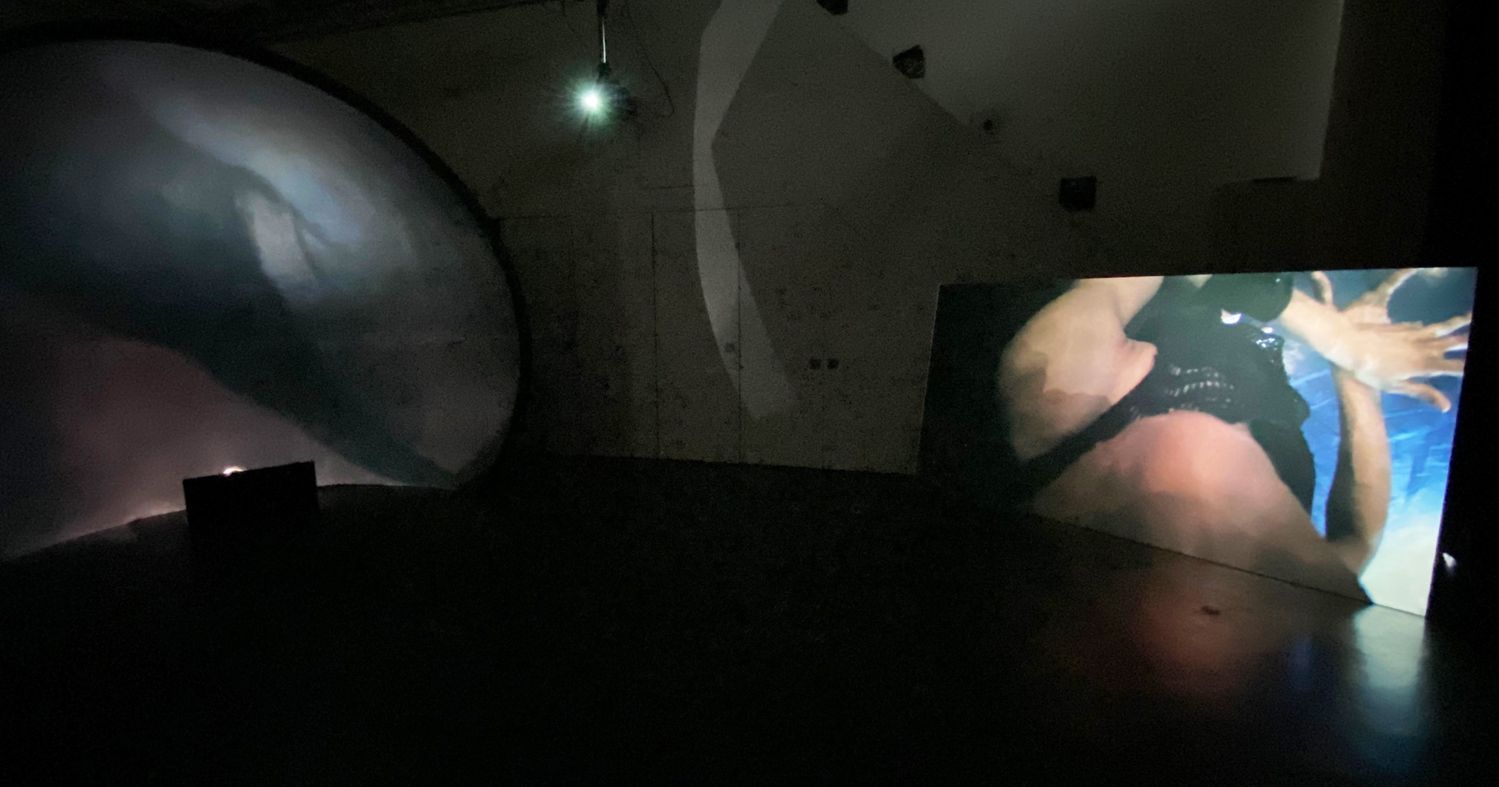

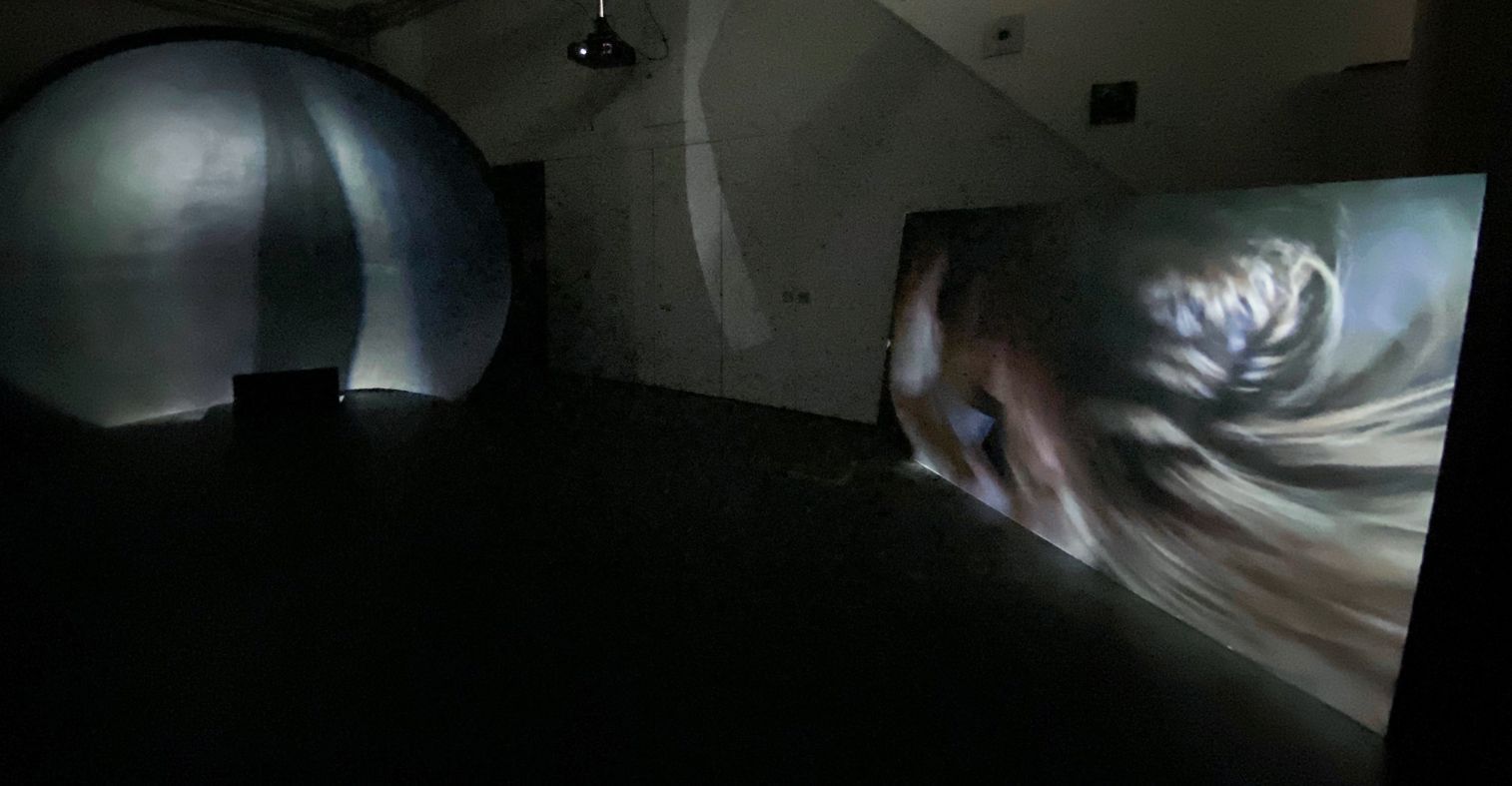

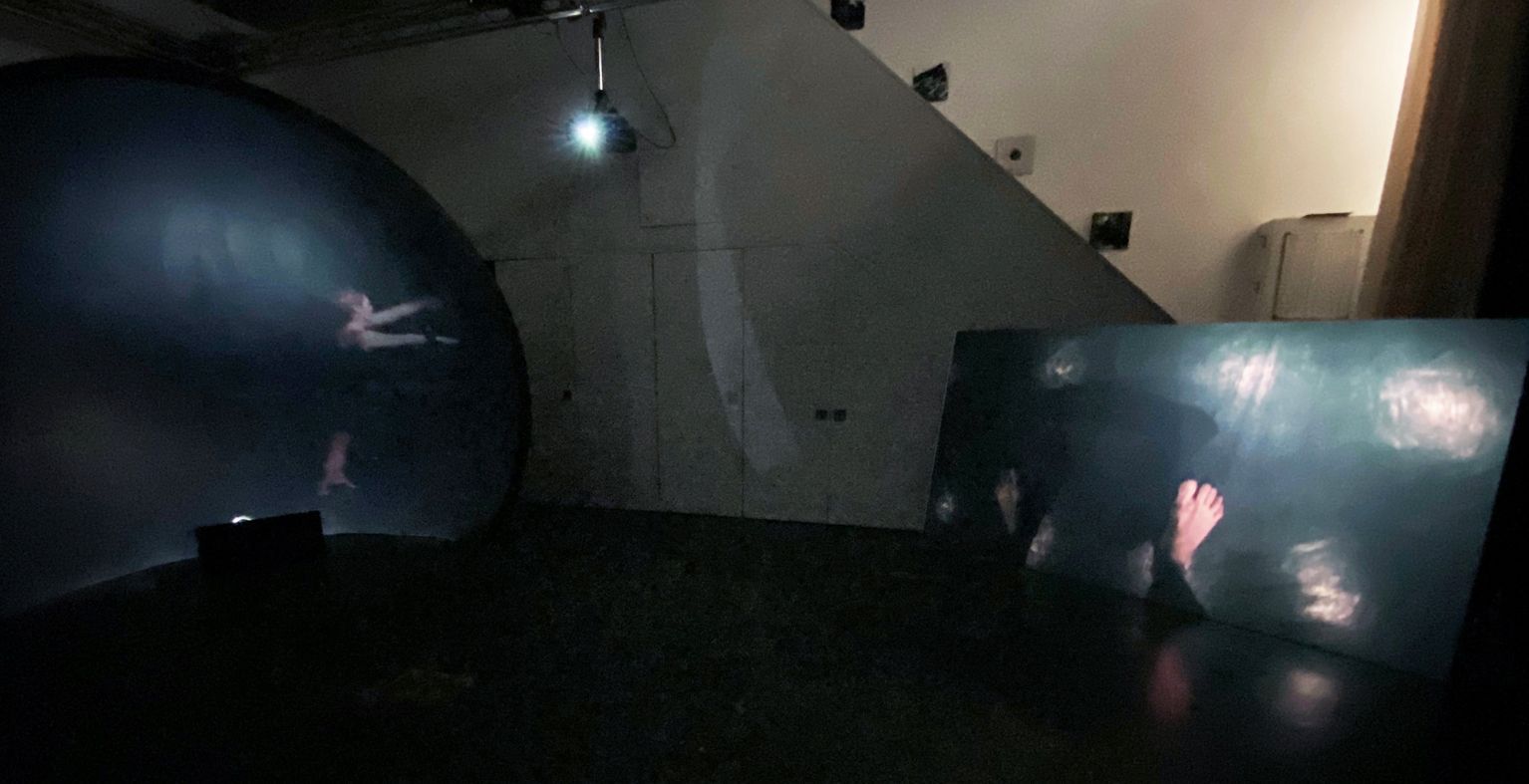

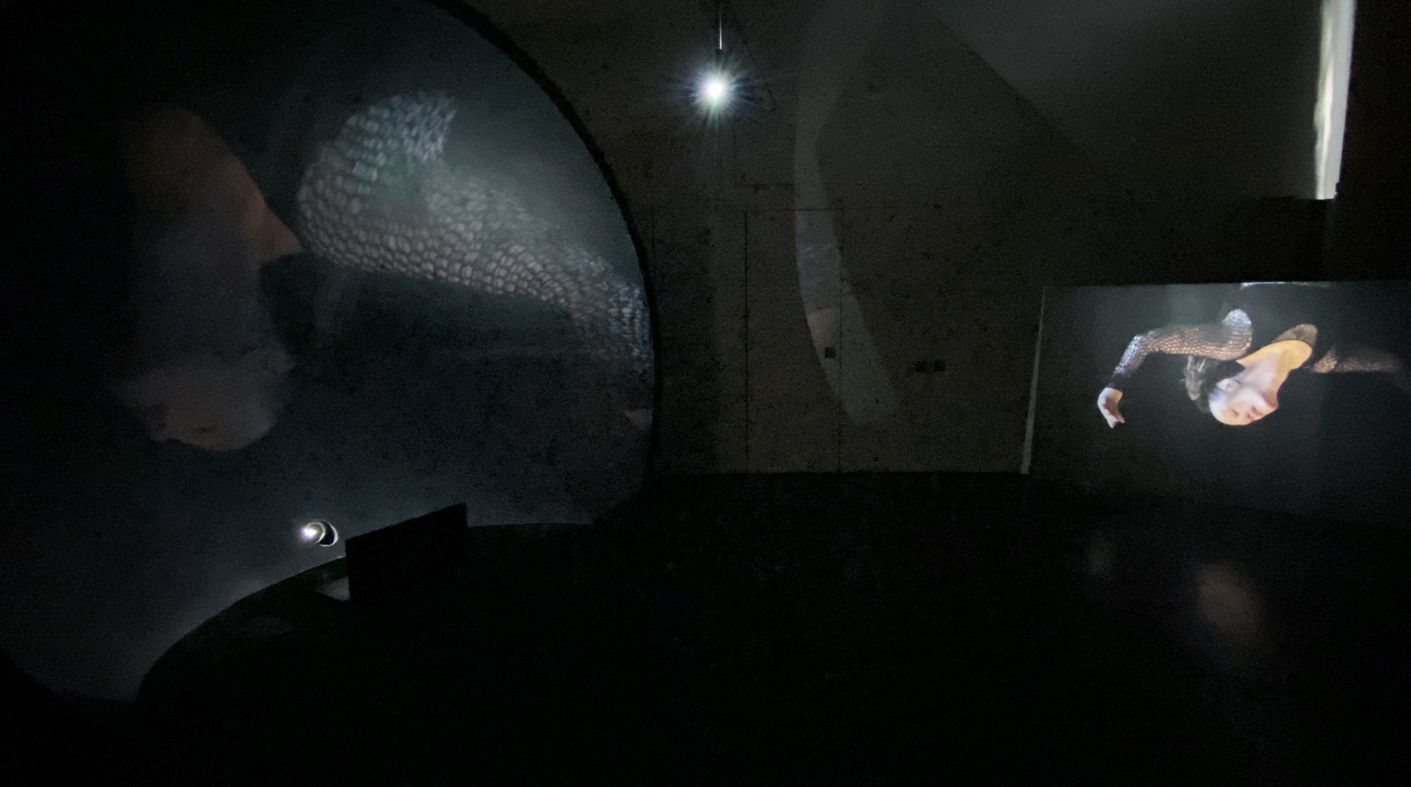

The three screens were also sculptural in presentation. One of the screens was a convex dome, the other a more traditional 16:9 sheet of black MDF leaning at an angel to a wall, and the third, a suspended screen in portrait format. So only one gave a complete viewing of what the film consisted of. The dome, because of its nature, produced an image that was quite ghostly while the portrait screen was a cropped version, offering only fragments of the performance. I really enjoyed this but it was really driven by the dome being already in the space. If I did the installation again I would have all 3 screens as 16:9, even if not necessarily the same size, to allow the editing to speak as intended.

Credits:

Choreography:

Choreography by Heidi Latsky in collaboration with the dancers

Camera:

Richard Ducker & Adam Simon

Sound:

Score by Heidi Latsky featuring MRI sounds and original music by X.I.M.E.N.A Borges and Ainesh Madan

Sonya Park, Dancer’s footsteps

Editing:

Richard Ducker

Dancers:

Jillian Hollis

Meredith Fages

Nico Gonzales

Henry Holmes

Leslie Taub

Roxanne Young

Heidi Latsky

Special thanks to:

Heidi Latsky

Adam Simon

Sonya Park

Edan Park

Joan Pierpoline & Chin Koock

David Cotterrell

Copyright

Richard Ducker 2025